Episodes

Friday Feb 14, 2020

California Charter Schools & Special Education

Friday Feb 14, 2020

Friday Feb 14, 2020

Every state has its own rules and regulations regarding charter school organization, configuration, and authorization. In California, charter schools are public schools that take Average Daily Attendance (ADA) dollars away from the school districts their students would otherwise attend. It is unlawful for charter schools in California to charge tuition to their students for this reason.

Like all other public schools in California, charters are obligated to abide by the same standards of compliance as any traditional local education agency (LEA) with respect to civil rights and special education law. While charters often like to think of themselves as "schools without rules," that really isn't true.

The truth is that some regulations are made easier for charter schools in California, while others are exactly the same as those that school districts are required to follow. The problem is that a lot of charter operators and their contracted vendors either don't know that, or they know it but don't care.

Understanding the charter rules for a single state, much less all states and territories, is confusing enough. Recognizing the abuse of those rules can be even harder for parents of students with special needs who require accommodations as a matter of civil rights, which can include an Individualized Education Program (IEP). In my experience, trying to enforce procedure in California's charter school universe usually ends in inter-agency political backstabbing and lawsuits.

To understand charter school compliance versus the climate of charter school politics in California, one needs examples. The one that most recently prompted my return to this issue was recently covered by The Camarillo Acorn in its February 7, 2020 article, "Online charter school faces laundry list of violations."

Online charter schools are even more challenged to comply with education law than brick-and-mortar charter schools. That said, for the chartering LEA in this particular case, Pleasant Valley School District (PVSD), to squawk about a lack of legal compliance on the part of the school to which it issued a charter, that being Peak Prep Pleasant Valley, is a grievous instance of the pot calling the kettle "black."

I can imagine Peak Prep's violations must be pretty egregious for PVSD to make a fuss about them in the media, and there is truly a fuss to be made as you can see from the article. But, the reality is that the Doctrine of Unclean Hands, at least as I understand it as a lay person, may preclude PVSD from saying a whole lot, which is possibly why it's addressing this situation in the media rather than a courtroom. So basically, black pots throwing stones at black kettles in glass houses, to mix metaphors.

I've had four cases from my advocacy caseload in the last couple of school years that have required due process filings, and three of them have been in PVSD. I have an active caseload that averages 20 students throughout the State, mostly in Southern California, at any given time. These are raw statistics; take them for what you will. But, to think these amoral jamokes are concerned about anything with this charter situation other than going down with the ship is foolish.

Read the article and you'll see there isn't a single, solitary concern expressed by PVSD for the welfare of students, parents, and community members. The only sentiment expressed is on behalf of allegedly overworked and underpaid district administrators who don't have time to clean up messes made by their charters. Not that imposing on district personnel to do what a granted charter requires of the charter school's staff is okay, but I get the same arguments from PVSD in response to asking it to give a kid with disabilities a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE).

This district gets itself into enough trouble on its own. A visibly non-compliant charter that won't get its act together, for which the district is ultimately responsible as the chartering LEA, can only shine a stronger spotlight of scrutiny upon the chartering district. In California, the chartering LEA is ultimately responsible for the conduct of its chartered entities.

In special education in California, if you have to file a compliance complaint or due process request for a charter school student, you have to name the complaint against the chartering LEA, not the actual charter school. This is because the LEA is ultimately responsible for the charter school's procedural compliance with special education law and providing FAPE to its special education students, regardless of how the charter school configures its special education services.

In California, when it comes to special education, charters can either be "schools of the district" for the purposes of special education, in which case the chartering LEA delivers all special education, or charters can be "LEAs" for the purpose of special education and take care of it themselves. Even if they organize themselves as LEAs for the purposes of special education, there is supposed to be oversight by the chartering LEA to make sure its obligations are met, but I've never seen that happen proactively. It's always a knee-jerk fit of hysterics on the part of the chartering LEA that had no idea what the charter school people were doing until a complaint came over the transom.

Based on the sordid history of charters in California thus far, I'd think that any school board reviewing a charter application that claims to organize the school as an LEA for the purposes of special education would exercise ten times the scrutiny as it would if the charter application sought to remain a school of the district for special education purposes. In my experience, the charters organized as LEAs for special education are only organized that way to keep the eyes of their chartering LEA out of their business.

Organizing the charter as an LEA for the purposes of special education is, in my experience, an effort to reduce oversight, not increase compliance. I've heard more than one charter operator claim over the years that they didn't want to be taken down by a non-compliant school district's special education department, so they chose to do it themselves, but then they have fewer resources than their chartering LEAs and can't actually deliver.

These are the charters that tell parents to take their kids with special needs back to their districts of residence instead of ponying up the resources to actually deliver on functioning as an LEA for the purposes of special education. Nothing prevents a charter from going to its chartering LEA and saying, "We have a unique situation and need your help," to address unusually demanding special education services, such as full-time nursing support for a medically fragile student, for example, but I've never seen a charter organized as an LEA for special education purposes do anything of the sort.

When you as a parent are jumping ship to a charter school because your kid with special needs is already getting shafted by your district of residence, this really doesn't help you out. Parents changing schools to avoid having to litigate their children's special education cases often find themselves tumbling over the edge of the frying pan and falling into a blazing fire. It's usually a lateral move at best, and a downgrade at worst. See our previous post, "Parents Who 'School-Hop' Risk Making Things Worse," for more on that.

However, PVSD seems to be the one shining the light on Peak Prep, here, which in my experience, usually means there is a fair amount of misdirection going on. By acting as the accuser, PVSD is diverting eyes away from its initial decision to charter Peak Prep in the first place. The last thing any school district wants, including this one, is an official inquiry into how they conduct their business, so when a charter draws this kind of attention, it's usually not good for the LEA that issued the charter.

But, it's not like Peak Prep's organizers' questionable history was unknown or that the quality of the charter application wasn't apparent at the time it was made. To quote PVSD's superintendent, "... the cast of characters is not new by any stretch .... The same group has done this before. They should and do know better." I say the same thing to myself every time I help an attorney draft language for a due processing pleading against PVSD on behalf of a child with disabilities.

The District's hypocrisy, here, is absolutely wretch-worthy, for sure, but this whole public display over proper education agency conduct is critically informative, and voters should be paying close attention to it. While the PVSD/Peak Prep situation is just one more log on the blazing fire of charter school politics in California, it's also a loud message for voters in Camarillo who are looking at the school board and wondering what it thought it could gain for the local community by chartering an online charter school in the current charter climate. Based on the behaviors of other districts, chartering online schools is about generating charter fees from students in other communities, not improving the options for local families.

There are two directions in which this story takes my mind, both of which are relevant and equal in importance. First, there is the litigation of the charter school wars that played out in the Santa Clarita Valley a couple of years ago. But, also, there is a privately owned outfit based out of the San Diego area that claims to help charter schools comply with special education law. In my experience, that's not actually what they do. When we start getting into the history of this issue, you will see San Diego come back up again later in this discussion.

First, I have to point out what happened in the Santa Clarita Valley, citing the publicly available evidence, but also sharing some first-hand information. That matter involved Acton-Agua Dulce Unified School District (AADUSD) as the chartering LEA and Albert Einstein Academy for Letters, Arts, and Sciences (AEALAS) as the charter school, which has no website because it went out of business due to fiscal insolvency at the end of the 2017-18 school year.

During the period of the Santa Clarita Valley charter school debacle, one of the students on my caseload was an AEALAS student, and nothing in the articles I can find online will ever come close to describing the hell that student and his family went through. All of the articles online are about fiscal mismanagement, which aren't untrue, but none of them speak to the horrific special education violations that were going on. We had to involve an attorney who, over several years, had to file for due process against AADUSD for AEALAS's improper conduct on multiple occasions.

The Santa Clarita Valley story is revealing and opens up many lines of inquiry for voters of all stripes. These issues affect the lives of our children, families, communities, and public education officials throughout the State. One of the most informative articles I've seen on that whole mess is, "How a tiny California school district sparked calls for a charter crackdown," by CalMatters.org.

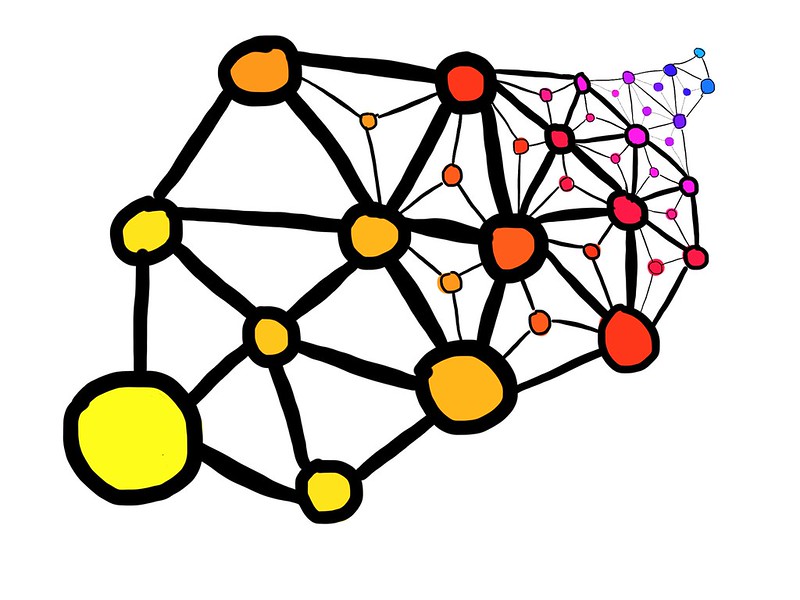

Rather than belabor all of it here, I encourage you to read the article. The infographic it includes is incredibly helpful. While it doesn't go into details about the special education issues per se, they aren't left ignored. The charter's inadequacies with respect to special education planning briefly identified in the article played out into absolute travesties in real life, before AEALAS ultimately closed down.

For example, none of the articles mention the AEALAS official who drank too much at his place of worship one night early during the school's first year, and basically told everyone there, most of whom were AEALAS charter school families, that our student's special education program was going to bankrupt the charter school and close its doors in the first year. This prompted the other charter parents from the same place of worship to send anonymous hate mail (signed with simply "Albert Einstein parents") to our student's family telling them they should pull out so his special education program wouldn't cost all their kids their charter school. So, way to go, religious people, for scapegoating a handicapped child to cover corrupt charter administrative fiscal mismanagement.

Clearly, no one had explained to the drunken administrator's constituents that categorical special education dollars can only be spent on special education costs, and none of that money could be spent on general education students in the first place. Our kid came with extra money above and beyond the ADA dollars that all students bring to a charter or LEA on a per-pupil basis, specifically to defray his special education costs.

What was really happening was that AEALAS was financially mismanaged from the start. That's why it couldn't get chartered by the six districts and two county offices of education to which it had applied before AADUSD granted it a charter. So they targeted a kid with costlier than normal special education needs, blamed the lack of funding on him, and sicced a pack of misinformed, emotionally underdeveloped adults on him and his family. It was an act of misdirection to make the charter's supporters think AEALAS was otherwise financially solvent all but for our student's special education program, when the evidence is pretty clear that it never was financially solvent at all.

Our anti-bullying efforts had to start with the adults at AEALAS, not the students. A non-public agency (NPA) bowed out early on and refused to do further business with AEALAS because the assistant principal at that time refused to abide by the scientifically designed behavior plan created for our student by the NPA, preferring instead to tackle him to the ground and scream in his face (our student was 7 at the time). He then attempted to treat the NPA's professional staffs in much the same way when they tried to get the charter to use positive behavioral intervention strategies, instead.

After the NPA's Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) tried to explain the science of what they were trying to do, the assistant principal became verbally abusive of them and physically threatening. He scared the crap out of them, actually. They took the matter to their NPA's ethics committee, which wrote a letter withdrawing from service on the basis of AEALAS's ethics violations, of which the NPA refused to be a part. I've never seen anything like it before or since in my entire career.

The real issue was cost. An NPA-designed and -implemented behavior program isn't cheap, though it's a heck of a lot cheaper than a lawsuit, and the taxpayers had already funded it. AEALAS was just woefully fiscally mismanaged; it was all about playing games with taxpayer monies provided for the purpose of educating children - a point that keeps getting lost in all the inter-agency infighting that's going on.

Also helpful, and linked-to in the CalMatters.org article, is a report published by the California State Auditor in October 2017, in which the players in the Santa Clarita mess featured prominently, titled, "Charter Schools: Some School Districts Improperly Authorized and Inadequately Monitored Out‑of‑District Charter Schools." I mean, they don't even wait until the opening summary of their report; they call it all out in the title.

You would think that other school districts in the State would have taken better notice of these developments and the outcomes they've produced. Maybe, however, that's one compelling reason why PVSD is reacting so strongly, now. If so, I have to give PVSD some credit for dealing with the situation within less than a year of issuing the charter, even if it does add to the smarmy politics of the issue.

These things, among many others, need to be sorted in public education. Ideally, PVSD wouldn't have issued a charter to an outfit capable of performing this poorly in the first place, but second best is admitting your mistake before it's too far gone, which PVSD appears to be doing, now.

Secondly are my concerns about the bad things creeping out the San Diego area with respect to charter school non-compliance with special education law. These charter violations place chartering LEAs in violation, whether the LEAs realize it or not.

In the PVSD/Peak Prep matter, one of the players in the current matter from the charter school was previously employed by another charter school that was shut down last year following charges filed against the owners of its parent organization, A3 Education, for pocketing $50M in taxpayer funds by the San Diego district attorney's office. For more information on that, see "How an alleged charter school conspiracy netted $50 million."

And, here's where it gets super creepy/interesting, depending upon your point of view. If you look on the Peak Prep website, it opens up by telling you that enrollment is closed. I would imagine so, because another page on the site lists all of the schools shut down by the court-appointed Receiver following the A3 lawsuit.

Now, supposedly, Peak Prep has nothing to do with A3, which is the company busted in the $50M charter scam. But, the Peak Prep Pleasant Valley principal, Shalen Bishop, is listed as the principal of University Prep, which is one of the schools listed as closed on the Peak Prep site. It and the other schools listed are A3 schools.

So, if that case isn't related to Peak Prep, why is that information on their site? That creates a link between shenanigans in the San Diego area to what's happening in PVSD. This supports PVSD's superintendent's previously quoted statement about this particular "cast of characters" having done this before and knowing better.

But, it gets richer. Also in the San Diego area is a privately owned company called Special Education Assistance and Technical Support (SEATS). SEATS doesn't have a website. The closest thing I could find was the LinkedIn profile for the wife of the husband/wife team that own and operate SEATS. There are also some job listing sites that come up when you do a search for SEATS, indicating that the agency is looking to hire resource specialists and speech-language pathologists.

But applicants be warned, SEATS reportedly does not cover travel time or mileage to dispatch their special education staffs all over Kingdom Come to serve students in independent studies and online charters. Even if a school is virtual, if a special education student of such a school still needs 1:1 specialist support to participate in instruction, or otherwise needs specialist services in person, the law requires the school to meet the needs of the child, not expect the child to warp themselves to fit the charter school's pedagogy. The whole point of special education is to individualize the program to meet the unique needs of the student.

SEATS has a reputation for making special education service decisions on the basis of how much they are willing to spend rather than individual student need. They also have a reputation of short-paying their vendors and speaking to them disrespectfully in IEP meetings and/or screaming at them outside of the meetings if they dare to recommend anything SEATS hadn't already approved for expenditure in advance of the meeting.

Needless to say, none of SEATS's employees are in a union of any kind. It's also not a coincidence that the teachers' unions in California are backing current efforts in Sacramento to take on this whole charter mess. Most of the charters in California, virtual or otherwise, do not have unionized certificated personnel, which has contributed to high turnover rates and disclosures among professionals about what they have been experiencing.

In the course of developing this post, I spoke with a colleague still employed by a virtual charter and she's just waiting for the State to come after her employer. All of the virtual charters are apparently starting to freak out because of all the accountability that is now coming their way. While she needs a job, she is also morally outraged by what she sees on a daily basis.

The stress of working for this charter is affecting her health and she has no union to turn to, but she also recently had to take her local school district to due process on behalf of her own child with special needs and it's not like they're going to hire her to work for them, after that. I've received similar feedback regarding work-related stress from former contractors of SEATS over the years that mirror what my colleague at the virtual charter was expressing to me the other day.

SEATS alleges to help charter schools comply with the special education regulatory requirements, but I've seen them mostly help charter schools try to dodge the special education regulatory requirements. SEATS personnel have been alleged to tell families that the charter school they chose cannot support their children's special education needs because they don't offer "those" kinds of services, so the families need to go back to their regular school districts.

The owners of SEATS once emailed me while they were on a cruise to tell me that the charter school in the case we were discussing didn't have the money to pay for the services we were requesting. Forget that the charter was paying SEATS to make sure they were provided.

As best as I understand it, SEATS basically tells its charter school clients, "Give us your entire special education budget for the year, and we'll make sure you don't get in trouble." However, the owners pay themselves out of that money, they have multiple charter clients, and they go on a whole lot of trips and cruises while kids with disabilities go without special education services that SEATS is supposed to provide, but "can't" because their charter clients don't have the money to pay for them.

From what I've seen, it's not that SEATS is trying to keep charter schools from making mistakes; it's that SEATS is participating in and profiting from the same charter money scams that are going on all over the State to hide mistakes, if not outright corruption, from authorities. They simply occupy the special education niche within this whole shameful legislative disaster.

One of the other charter systems being scrutinized, now, is the Inspire chain of charter schools. I had a student on my caseload a year or two ago who was an Inspire student. His online/independent study program was chartered by none other than AADUSD. Inspire also has programs chartered in the San Diego area, where the A3 $50M matter was tried. Now Inspire is under scrutiny for, among other things, lack of transparency, and I'm not the least bit surprised.

Like most of my other special education students accessing in-home instruction through independent study and/or online instruction, my Inspire student's situation wasn't about school of choice. The brick-and-mortar setting wasn't accessible to this student because of his disabilities, making his living room the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) in which he could receive and benefit from instruction. He had previously been in an independent study charter that used SEATS for special education and, when that didn't work out, they went to Inspire.

When things get so extreme that instruction in the home is the only way for a student to access education in a regular school district, you get a doctor's note stating that it's medically inadvisable for the student to attend a regular school and the IEP placement can be changed to home/hospital. The only placement more restrictive is a 24/7 residential facility with a school on its grounds. But, because every kid's living room is the general education classroom in an online or independent study program, it's not considered restrictive at all.

Because the general education "classroom" and special education "classroom" are the same thing in an online or independent study program, trying to write an IEP for a kid in such a program is generally a nightmare of technicalities and questions of procedure. Then there are the fights over where special education and related services will be provided.

Even though school districts will hire staffs to provide in-home services as needed to facilitate access to instruction, almost every online and independent study program I've ever encountered refuses to send anyone to the home for any special education purpose other than assessment, and even then, sometimes not. So, even if you've got a kid whose disabilities make it impossible to get them to participate in instruction and they need in-home BCBA support to overcome that behavioral challenge, most independent and online charters won't even think of sending over a BCBA or will only do it upon threat of complaints or litigation.

These online and independent study programs will try to get IEP services pushed out into the community rather than into the student's home, which mostly has to do with the insurance costs and the related liability of sending teachers and specialists into people's homes. They'll try to make the parents drive their kids to meet teachers and specialists in the community when these kids are only in home instruction because getting them out of the house is often so hard. One of my past clients would drive to the next town over with their kid to accommodate the fact that SEATS wouldn't pay their special education teacher mileage or time to drive to their community.

Instead of individualizing the instruction, online and independent study schools tend to use their pedagogy as their excuse for not tailoring the IEP to the individual student, as required by law. So, the bottom line to all of this is that parents of children with special needs in California need to think long and hard about whether a charter school is appropriate for those children, particularly an online or independent study charter.

It's not that charter schools, even the online and independent study ones, in theory, are a bad idea. It's that they are improperly regulated in California, so they are becoming something other than what they were intended to be. In no small part, this is because certain elements out there don't want their kids going to school with "those other kids," and are trying to twist the charter system into a system of segregation.

Whoever happens to be "other" relative to the parents practicing such bigotry and teaching it to their kids, with the help of the dysfunctional charter system for profit, depends on the parents. Sometimes it's racism. Sometimes it's religious extremism. Other times it's socio-economic classism. Sometimes it's people who don't want to be criminally prosecuted for not sending their kids to school and couldn't possibly care any less than they already do about education.

There are enough people out there who don't want to abide by public education's true intent and will try to twist the system to fit their ill-intentions to do obvious harm. Such has been the case with charter schools in California, which is finally prompting a louder call for more appropriate regulations. The concern for many is all kinds of vendors profiting from the existing dysfunctional system without delivering actual educational outcomes, which circles us around back to SEATS.

The situation with Peak Prep Pleasant Valley speaks to the running concerns I've had for years about how SEATS is funded. PVSD is asserting that Peak Prep violated the California Education Code and the State's labor laws by giving away its control of "hiring and termination decisions" to a third party contractor, called Educational Staffing Services (ESS). It is further asserting that Peak Prep "engaged in fiscal mismanagement" by giving over its administrative operations to yet another 3rd party contractor, Accel Schools, which is owned by the same guy who signed the contract between Peak Prep and ESS as ESS's CEO.

According to PVSD, Peak Prep gave Accel control of its funds and failed to complete requested financial documents. PVSD can't see how Peak Prep is using its funds because its operating budget is "obscured by a lump sum payment in exchange for the program services, all delivered by Accel." This is, to the best of my understanding, the same model as how SEATS gets funded.

Like Peak Prep giving its money to Accel in a lump sum, which then shows up in its budget as a single line item with no detail on how that money was spent, SEATS's clients are giving it lump sums that represent their entire special education budgets for the school year. I have to wonder just how many details they are sharing with their charters and how many of those details the charters are sharing with their chartering LEAs about where that money is going. I have reason to suspect that it's paying for cruises rather than special education services.

To be fair to vendors and contractors who serve charter schools in California, it's honest to say that the laws are a mess and even the most well-intended vendor is at risk of getting into trouble over finances just because of how poorly regulated charter schools are in California. Rabbi Mark Blazer, who spearheaded the failed AEALAS endeavor in the Santa Clarita Valley, was quick to point out "bad charter policy" in California, and he's not wrong that California's charter policies are bad.

It's just that most of the charters out there, in my experience, see the bad policies and weak regulations as exploitable opportunities for profit. The children and families horribly affected by their actions are just collateral damage, not the intended targets. Students are just a means to a financial end to these people. The harm done is all the same regardless of intent, and it's far-reaching.

A whole bunch of very crooked people have now stolen way too many taxpayer dollars in California that were invested by the public into education. California has created a charter school system that is more about moving money around, mostly into the pockets of the wrong people, than educating students. While Betsy De Vos may find that acceptable, most Californians - heck, most Americans - do not.

A system like this entices the least savory people on the planet to parasitically attach themselves to it wherever there is an exposed spot, such as the loophole-laden charter laws in California, and suck the system dry before it realizes how much it has hemorrhaged. The cases making it to media make that clear. The chief perpetrator in the $50M A3 scandal is an Australian national.

The unspeakable number of dollars spent on litigation, whether its families suing to get special education services or school districts suing each other over ADA dollars, takes funding out of the classroom and creates overworked and underpaid certificated personnel. This is a voter issue that isn't getting enough attention, but with the election coming up later this year, Californians will have the chance to hold the State and their local school boards accountable and elect or re-elect officials who will clean up these messes in a timely, responsible way.

Sunday Jan 12, 2020

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports in Special Education

Sunday Jan 12, 2020

Sunday Jan 12, 2020

In memory of Cedric Napoleon

I wasn't going to write on this topic quite yet, but I'm working on a case right now that has me upset over public agency mismanagement and misconduct that has resulted in the physical abuse of our nonverbal student with severe special needs and God only knows how many other students within this public education agency. It reminded me of a lot of things, including our organization's founding and the protective purpose KPS4Parents has always served as student and family advocates.

I maintain my list of topics to write about as draft posts on the backend of our site, sometimes just as a title, sometimes with a brief description, as the ideas come to me and, when I go to write, I have them more or less organized in my head in the order I want to write them. But, sometimes, like now, something happens that makes one of the topics leap up to the top of the list.

I am currently providing paralegal support to an attorney on a case in which our student has gone for years without behavioral interventions in her IEPs after previous years of successfully benefitting from such IEP interventions. She has regressed to the point where she was behaviorally 10 years ago, before receiving any appropriate behavioral interventions at all.

The educational neglect in this case rises to the level of physical abuse. The school district's bumbling ineptitude at the expense of our student's welfare has been nothing short of galling. Our student is now sitting safely at home waiting for her case to be either adjudicated or settled but without the benefit of any instruction or related services until it's resolved.

Which takes me back to the founding of KPS4Parents and the event that was the last straw that compelled our founder, Nyanza Cook, to start KPS4Parents. In 2002, I was a lay advocate in private practice helping families of students with special needs, and Nyanza hired me to help her with her step-son's case, which is a story unto itself for another day. It's how we met and these were the early days. It was the context we were in at the time.

Nyanza hails from Killeen, Texas near Fort Hood, the largest U.S. Army base in the continental United States. While diversity has been tolerated, if not embraced, within the U.S. military in many instances, outside of the military base in the rural areas of Texas, diversity is not so much appreciated. Killeen Independent School District (KISD) has historically operated separate schools for students with "behavioral problems," most of whom have been African-American or Latino. The quality of special education in KISD has been historically abysmal, particularly for students of color, which is how it's misconduct led to our organization's founding.

In 2002, a young man named Cedric Napoleon was attending a Special Day Class (SDC) at one of KISD's special schools for students with "behavioral problems." Cedric was a foster child living with his foster mother, Toni Price. He had experienced severe trauma in early childhood, including deprivation of food for days that led to a food hoarding behavior and other behavioral challenges. He was in special education under the Emotional Disturbance (ED) category and his SDC was supposed to be configured specifically for students with ED issues.

Also in the classroom at the time was Nyanza's nephew. On one fateful day in March 2002, Cedric was suffocated to death by his classroom teacher during a prone restraint. He was not being violent towards others, trying to run out of the classroom, or hurting himself when she restrained him. He was being non-compliant and she took it as an affront to her authority. She pinned him face down on the floor out of hostile rage and when he said, "I can't breathe," she replied, "If you can speak, you can breathe." He expired shortly thereafter as Nyanza's nephew and his classmates watched on in horror.

That night, Nyanza got a hysterical phone call from family members gathered at her parents' house in Killeen. They knew she was talking about starting a special education advocacy organization and had been advocating for her step-son in California. They put her nephew on the phone with her and all he could say in a dazed voice was, "They killed him, Auntie. They killed him." He was terrified to return to school after that, and never did. His life has been one of despair and tragedy ever since.

The day Nyanza's nephew witnessed Cedric's murder in his classroom by his teacher, he was already there because he had his own ED issues. To add the trauma of witnessing Cedric's murder to his own pre-existing special education needs, in the place that was supposed to help him overcome his pre-existing special education needs and at the hands of the person who was supposed to help him, was just too much.

More than one life was destroyed that day. Cedric's classmates witnessed his murder in that ED SDC and were affected for life in ways that could only lead to more suffering for them. The District's students most vulnerable to trauma were severely traumatized by one of the most grotesque abuses of their trust possible. They witnessed their teacher kill a classmate for daring to defy her authority.

Nyanza called me that night as soon as she got off the phone with her family and told me what they had told her. She and I agreed that when teachers were murdering our babies in plain sight of our other babies (we have an it-takes-a-village mentality, which makes all babies our babies), we couldn't stand idly by. The death of Cedric Napoleon was the final straw that compelled Nyanza to go through with starting our organization, she asked for my help, I said "Yes!" without hesitation, and we had our paperwork in order by June of 2003.

In Cedric's case, to make matters worse, once his life had ended, so had his foster mother's legal authority to act on his behalf as a parent. She could not pursue justice for him because she lacked the legal authority and the foster care system did little to nothing about it. Cedric's killer was never tried for murder. She was never subject to any disciplinary action by the public education system in Texas.

On May 19, 2009, Toni Price finally got her chance to do something about what had happened to Cedric. The Education and Labor Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives was being presented with a report of the findings of an investigation the Committee had previously ordered to have done by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) regarding the use of seclusion and restraints in public schools. There had been a fairly recent similar study conducted of private schools that produced shocking and horrifying disclosures as bad as Cedric's or worse, and the Committee had wanted to know if these problems were also pervasive in our nation's public schools.

The GAO report started circulating among those in my professional circle online shortly after the hearings and ultimately found its way to me. I remember reading through it and getting to the section describing what happened to Cedric and going, "Wait a minute. I've heard this story before ... OMG! This is the kid from Nyanza's nephew's class!" I immediately forwarded the report to Nyanza and either called or texted her to follow up. At some point we ended up on the phone and she was flabbergasted to see Cedric's story spelled out in the report. It was the same student she had told me about back in 2002.

In the course of conducting its investigation, out of all of the cases of problems with seclusions and restraints that GAO examined, Cedric's stood out as particularly horrifying, in no small part due to the fact that his killer had never faced any serious consequences for killing him at the time of the investigation. The investigators searched for this teacher when their investigation revealed that she had faced no consequences and, shortly before the date of their presentation to the Committee, found that she had relocated to Virginia and was running an SDC on a public school campus that was only a 45-minute drive away from where the Committee was convening to hear the presentation of their report.

There was no effort to conceal the outrage that several Committee members expressed over the fact that this woman had not only killed an ED student in the ED SDC where she was supposed to be helping him get better, but that she faced no consequences and was able to get credentialed in at least one other state because the fact that she had killed a student didn't follow her on her record. They openly referred to Cedric's death as a murder.

The Committee's disgust is exposed during the hearing (click here for video of the full 2-hour hearing), and I share that disgust. It is disgusting; disgust is the only healthy response to what this woman did. Rep. Rob Andrews (1:22:22 - 1:28:16 of the hearing video), Rep. Lynn Woolsey (1:53:02 - 1:54:18 of the hearing video), and Rep. George Miller, Committee Chair (1:55:21 - 1:57:44 of the hearing video) had particularly candid things to say and there was bipartisan heartsickness over the whole thing.

The only reason Cedric's killer was found was because of the GAO's investigation. Had it not conducted it, a known killer would have been allowed to remain as a fox in a henhouse, circulating among the same types of individuals upon whom she had preyed before. Their parents had no idea they were sending their vulnerable children off to a child killer each school day. Even now, almost 11 years later, the thought still makes me shudder with horror.

The Committee's take on the situation was influenced in no small part by the testimony of various witnesses produced by the investigators in support of its findings. Among those asked to testify was Toni Price, Cedric's foster mother. Her testimony was compelling; even now, it still makes me cry.

Toni argued for a national, if not global, directory of teachers found guilty of child abuse for education agencies to use for screening teaching applicants, and she did so from the most informed position possible. She spoke as the primary caregiver of a child with mental health needs killed by the person entrusted to address them every day at school, but with no legal recourse to do anything about it, leaving advocating for that child and protecting others like him to no one. Only the fluke of a Congressional investigation at the right time on the right topic exposed what happened, and Toni took the opportunity to say what needed to be said.

Which brings me back to the topic of this post and podcast, which is the use of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in special education. Subsequent to the May 2009 hearing, GAO began gathering additional information and the U.S. Department of Education began promulgating guidance and technical information regarding PBIS. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Education produced the Restraint and Seclusion Resource Document.

In February 2019, after 10 years of collecting data on the use of seclusion and restraints in our public schools, GAO produced another report and another hearing was held during which the last 10 years' worth of data collected and analyzed were presented to the Committee. Witnesses gave testimony, provided additional evidence, and answered questions. You now can look up the CRDC data for your own school district on the CRDC site.

Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Department of Education announced an initiative to address the inappropriate use of seclusions and restraints in our public schools. Just this last December, four members of the U.S. House of Representatives proposed a bill, HR 5325, referred to as the “Ending Punitive, Unfair, School-based Harm that is Overt and Unresponsive to Trauma Act of 2019” or the “Ending PUSHOUT Act of 2019," which seems like way too poor of a word choice for a name just to create an acronym, but the body of the bill still nonetheless prohibits seclusions and restraints and includes other regulations pertaining to behavioral interventions.

HR 5325 is still a bill pending before the Education and Labor Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. It was introduced just last month, so obviously nothing has happened with it, yet. Congress has been a little busy lately and the last time the Committee tried to pass legislation to address seclusion and restraints in 2009, it passed in the House only to never see the light of day in the Senate. That's likely to happen again, now, with our current configuration of Congress, but the effort still needs to be made.

What GAO reported in the most recent hearing was that there wasn't enough data in, yet, regarding the efficacy of Education's efforts to promulgate PBIS technical information and guidance among the public schools or the degree to which the schools that availed themselves of it found it beneficial. In controlled research situations in which implementation fidelity was maintained, PBIS was proven to work, but how well public schools actually implement it with success in the absence of researcher oversight and fidelity checking remains to be seen.

What seems to be the case, and the whole reason this issue is before the House Education and Labor Committee, again, is that there is an obvious need for federal oversight and regulation, here. There is a lack of consistency from state to state as to how behavioral interventions are to be implemented in schools. Some states have regulations regarding seclusions and restraints in schools and others do not. Even those states that have laws in place don't provide for adequate enforcement of those laws.

The lack of built-in accountability has made it possible for horrible situations to happen. And, they continue to happen. The only way the public school system is held accountable in situations like these is when individual families take legal action. Hence, the case I'm now working on that has made these issues spring to life for me, once again, much to my deep disappointment.

Educator and support staff training, or a gross lack thereof, more specifically, is often at the heart of these cases. But, so is the lack of teacher accountability and the degree to which educators tend to cover up each other's tracks, even if it means a child dies in the process.

The fear of talking usually goes to fear of losing their jobs, fear of reprisals from their co-workers, fear of being held accountable for the actions of others, fear of getting in trouble for the same thing for which someone else is getting in trouble because they've done it, too, and has to come with a tremendous amount of internal conflict. Only sociopaths could smoothly walk that rocky landscape without being troubled by the experience.

The willingness of school administrators to let something as horrible as student traumatization, physical injury, and/or death by the hands of teaching staff and aides in the learning environment get swept under the rug and hope nobody notices, if not actively seek to conceal it, is repugnant. There is a lack of professional integrity in the public education system that can reach sickening proportions, and these cases are examples.

So, I really don't have an upbeat ending for this post and podcast. I'm pretty not okay with what I'm still seeing going on with respect to seclusion and restraints in public schools in California, which is supposed to be the most progressive state in the country. It's particularly bad in rural communities far away from specialists and adequate facilities, particularly when those communities are mostly made up of low-income households.

In some cases, like the one I'm working on now, the student has experienced nothing short of absolute barbarism. It shouldn't take people like me helping to hold the public education system accountable after the fact. The answer is prevention. In the absence of any guidance in the student's IEPs as to how to address her behaviors, she was repeatedly secluded and restrained by teachers and aides who didn't know what else to do.

This was all just up until a few weeks ago, which is why she's now safely at home but without any instruction or related services until her attorney, in collaboration with me as his paralegal and the experts we're bringing onto the team, can get this mess cleaned up. It just sickens my heart that after all the years that I've been doing this work - 29 years this coming June, mind you - this is where things are still at. In the most progressive state in the Union, we're still secluding and restraining non-verbal students who are struggling to communicate their wants and needs. It puts bile in the back of my throat.

Tuesday Dec 31, 2019

Tuesday Dec 31, 2019

Image credit: Elco van Staveren

Image credit: Elco van Staveren

Special education is heavily regulated to protect the rights of eligible students to individualized educational planning, but complying with the regulations is easier said than done. The operational design of most public schools is over 150 years old and based on the mass production mentality of a factory, having been created during the Industrial Revolution. By contrast, the applicable special education laws were first passed in the 1970s, accounting for only the last 1/3rd of the current American public education system's history.

Trying to implement the individualized educational planning called for by special education law in an environment created for the purpose of mass instruction is like trying to build a custom piece of furniture on a moving assembly line. In the early days of special education, this meant removing students from the general education setting to special education classes, effectively choosing to build a custom piece of furniture in a specialized workshop rather than on the pre-existing assembly line.

The problem, however, is that pieces of furniture do not have civil rights. It's one thing to segregate inanimate objects according to how they are constructed. It's another thing to segregate human beings according to whether they need changes in how they are instructed due to disability.

Because special education students have legal protections against being segregated out of the general education setting simply for having a disability, integrating individualized educational planning into a mass instruction environment becomes that much more complicated for special education students who are educated with their general education peers for all or part of their school days. The complexities of individualizing educational programs for each student are seemingly infinite, given all of the relevant disability-specific considerations plus all of the ecological factors involved in each instructional setting.

However, science - specifically research conducted by educational psychologists and their colleagues - has been attempting to keep up with the demands created by various types of unique student needs, including disabilities of all kinds. While it all hasn't been figured out for every situation by any stretch of the imagination, there is still a wealth of information from education research that never makes its way into the classroom, much less into individual IEPs.

That's a problem because Title 34, Code of the Federal Regulations, Section 300.320(a)(4) mandates the application of peer-reviewed research to the design and delivery of special education on an individualized basis, unless it's not practicable to do so. No one has yet defined what "practicable" actually means, so it's still up for debate.

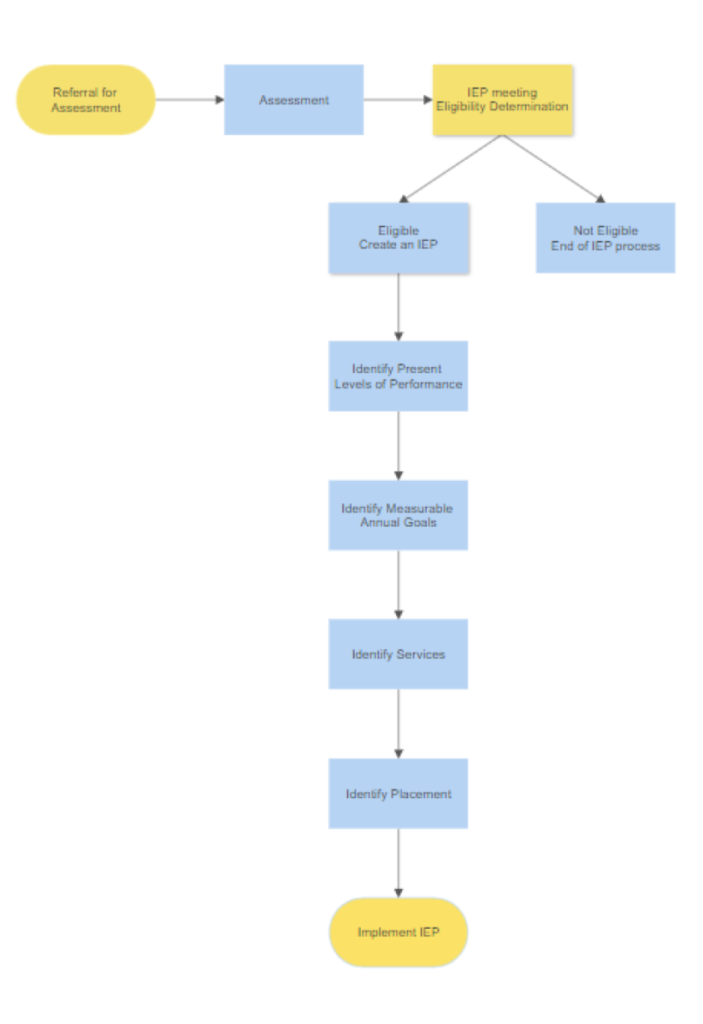

The history of how all this science ended up being codified within the implementing regulations of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), has been summarized in our last blog post, "The Fundamental Flow of IEP Creation," so I won't repeat it here. You can review the impact of PARC v. Pennsylvania in that post to inform references to it, here.

The point is that the applicable science has always been written into any serious redress to the educational needs of students with disabilities after having been deprived educational benefits by the public school system. In PARC v. Pennsylvania, a psychologist with extensive experience working with children with intellectual disabilities and an attorney committed to representing the interests of children with intellectual disabilities were jointly appointed by the federal court to serve as special masters to oversee the implementation of appropriate interventions to students with intellectual disabilities in Pennsylvania's public schools as part of the settlement that was negotiated between the parties. The settlement included federal court oversight by way of the court-appointed special masters.

The historical foundations of the requirements for measurable annual goals in IEPs pursuant to 34 CFR Sec. 300.320(a)(2) and the application of the peer-reviewed research to the delivery of special education as mentioned previously can be traced directly back to PARC v. Pennsylvania. There has never been a time when the law did not expect the delivery of special education to be informed by anything other than evidence-based practices developed from the peer-reviewed research.

From the moment the first laws were created to provide special education to all eligible children in the United States, science was built into its design. Federal Supreme Court case law has established that Congress expected procedural compliance with the IDEA to all but guarantee compliance with the substantive requirements of the law when it authored and passed what is now the IDEA. Specifically, the case law states, "...the Act's emphasis on procedural safeguards demonstrates the legislative conviction that adequate compliance with prescribed procedures will in most cases assure much, if not all, of what Congress wished in the way of substantive content in an IEP." (Board of Educ. v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176 (1982))

Congress intended for the applicable science to guide the special education process for a number of good reasons. First, using science means using what everybody can agree actually works under a given set of unique circumstances, to the degree such is known. There is evidence - proof - that under the explicit conditions that were tested, a particular method of intervention works or doesn't.

Because every special education student presents as a highly unique individual such that their learning needs do not conform to conventional instruction, they require highly individualized instruction that is tailored to each of them, respectively. There is no one-size-fits-all method of intervention proven to work in special education contexts. What is proven to work is writing up a unique program of instruction for each individual student. That is the evidence-based applicable science, that is the bottom line requirement of the applicable federal law, and this has been known and federally regulated since 1975.

This, therefore, begs the question as to why so much of special education is based on subjective opinions, ballpark estimations (often underestimations), and fad theories about learning rather than science. There's been a lot of research into why the research isn't being promulgated for use in public education and politics has a lot to do with it.

Applying the research means upgrading facilities, retraining teachers and their support staffs, buying new materials, and paying for more specialists. Further, it's often necessary to purchase all of the research materials necessary to inform any kind of evidence-based program design and hire someone who knows how to translate the research into a data-driven educational program. For highly paid top agency administrators who get compensated on the basis of how much money they don't spend rather than how many students they do get educated, applying the research means spending money, and that's no way to get a raise in that kind of institutional culture.

Another concern of many public education agencies is accountability. When using evidence-based practices in the delivery of special education, one can't ignore the body of research that supports that the data collection and analysis methods used in Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) are the most reliable methods of data collection and analysis used in any special education context (Drasgow, Yell, & Robinson, 2001; Kimball, 2002; Yell & Drasgow, 2000). The problem for some education agencies is that valid data collection means all their missteps will be captured by the data. If they aren't actually implementing the IEP as written, the data will reflect that, exposing the agency to legal consequences.

People often mistake ABA for a treatment for autism, but this is not the case. It is true that behavioral interventions using ABA can be effective at addressing behavioral challenges with students who have autism, as well as any other human beings with behavioral challenges, but it can also be used as an instructional methodology and as a tool to determine if learning has occurred and, if so, how much. That is, it is excellent at measuring progress towards a clearly defined outcome, such as a measurable annual IEP goal.

The Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (ABC) data collection methods used in ABA naturally lend themselves to measuring progress towards IEP goals. This is how it works: a stimulus (Antecedent) is presented to which the student responds with a specific Behavior, which immediately results in an outcome (Consequence) that either increases the likelihood of of the behavior happening again (reinforcement) or it doesn't (absence of reinforcement or punishment).

Most people in special education are at least familiar somewhat with using this approach to dealing with inappropriate behaviors. You don't want to deliver a reinforcing consequence when an inappropriate behavior occurs. Instead, you want to reinforce a more appropriate replacement behavior that still meets the student's needs; the behavior was happening for a reason and you can't leave its function unaddressed or a new behavior will just develop around it. Treat the cause, not the symptom.

You only resort to punishing the undesired behavior when reinforcing the desired behavior is not sufficient at extinguishing the undesired behavior. Presenting reinforcement for doing what is expected and withholding reinforcement for doing what is not expected is usually a pretty powerful strategy for positive behavioral interventions.

When using ABC data collection and analysis on the fly during instruction, your thought process is a little different. When you're looking at whether a student is learning from the instruction you are providing, especially when working with students who have significant impairments that limit their expressive communication skills, sometimes it's the raise of an eyebrow, the turn of a head towards you with eye contact, or the smile or grin that tells you whether or not you're getting through. There is still an Antecedent (the delivery of your instruction and/or check for understanding), a learning Behavior (the student's response to your instruction and/or check for understanding, whether verbal or not), and a Consequence (praise for learning or encouragement for trying) that increases the likelihood that the student will remain engaged and continue to participate in the instruction.

When using ABA-based data collection methods to measure for IEP goals, so long as the goals are written as math word problems based purely on observable learning behaviors, it's pretty straight forward. Take for example this goal, which is purely made up for illustrative purposes: "By [due date], when given 10 calculation problems using multiplication of double digit numbers per trial, [Student] will calculate the 10 problems with at least 80% accuracy per trial in at least 9 of 10 consecutive trails within a semester, as measured by work samples."

This is easy. There are 10 problems per trial. The student needs to get at least 8 out of 10 problems right per trial (measure of accuracy) in at least 9 out of 10 consecutive trials (measure of consistency) within a semester (measure of time) in order to meet the goal. Nothing is left to guesswork. Everything is represented by an increment of measure.

What ruins a goal out of the gate is basing any part of it on internal thoughts and feelings experienced by the student. Never start a goal with language like, "... when feeling anxious or angry ..." or "... when presented with a non-preferred task ..." You can't trigger the onset of measurement based on something you can't observe. You only know what the student is thinking or feeling once they express it in some way.

There is no way to get in front of the student's expression of their thoughts or feelings to prompt their behavior in an appropriate direction because there is no way to know what the student is thinking or feeling before they act. Other people's thoughts and feelings, including those of special education students, cannot be observed or known by other people. No credential in special education imbues special education personnel with clairvoyance. By the time you know what the student is thinking or feeling, it's too late to influence how they act on those thoughts or feelings; you only know because they've already acted.

The same goes for preference. Preference cannot be observed and it can vary from day to day, or even moment to moment, for a lot of special education students. What is preferred at one time will often not be preferred at others. Eventually it is possible to have a good idea of what is not preferred by a student, but then confirmation bias can enter the picture and you see what you expect to see, not realizing you're prompting it according to your preconceived expectations.

What makes more sense is to write goals that do not target what are referred to in ABA as "private events," but rather to expected behaviors. For example, a common behavior targeted in the IEPs of students with challenging behaviors is work refusal, which is to say non-compliance with task demands. A teacher will assign a task and, if the student is non-compliant, they will either passively sit there and just not perform the task; do something else passive instead, like doodle or read a book; engage in distracting or disruptive behavior, like play on their phone or talk to their neighbors; or engage in outburst behaviors, possibly accompanied by leaving the room (eloping).

It's usually pretty easy to figure out if there is a pattern to the types of tasks assigned and when non-compliance occurs such that preference can seem easy to identify. But, trying to rely on that for the purpose of measurement is like trying build a house on shifting sands because someone's preferences can change so quickly.

The language that I see most commonly used in goals that work around the issue of private events reads more or less like this: "By [due date], when assigned a task, [Student] will either initiate the task, ask for help, or request a 2-minute break within 60 seconds of the task being assigned in at least 8 of 10 consecutive opportunities as measured by data collection."

This makes things easy. Regardless of whether the student has a personal preference or not for the task being assigned, they will either start the task, ask for help with the task, or take a short break and get it together before they come back to the task.

Some students have processing speed delays that interfere with their ability to get started right away. They need extra time to process the instructions so they understand what you want them to do. Sometimes that extra little break is all they need to get there independently. It just takes them a little longer to think it through and make sense of what you want from them before they know what to do and can start. Other students get emotionally overwhelmed and just need to go get a grip before they tackle the expectations being placed on them. Yet others take longer to stop one activity and transition to another one. That short little break can buy them the time they need to process the mental shift of set and orient themselves to the new demands being placed on them. Other times, students just don't understand the expectation being placed on them and need clarification.

In any event, if there's a problem, the goal provides a solution; otherwise, the student just needs to perform the task as assigned. Further, the language of this example goal can be modified for a student to provide for alternative acceptable responses and/or a different response time.

With respect to measurability, there is no guessing about what anybody is thinking or feeling in a goal formatted this way. Measurement is triggered by the delivery of a task demand (the assigned task) and is based on whether any of the described acceptable outcomes occur within 60 seconds. All of the elements of the goal are measurable.

Further, a goal written this way follows the ABC format of ABA. First an Antecedent is presented (the task demand), then one of three acceptable Behaviors (task initiation, request for help, request for break) occurs, then an appropriate Consequence (completion of the task, delivery of help, or receipt of a short break) is immediately forthcoming. Everything that needs to be measured can be observed. The observable criteria are easily represented in increments of measure. It's black-and-white without making any assumptions about a student's thoughts, feelings, or preferences.

So, having said all of this, how does this get us to the point of the article, which is how parents can successfully advocate for the application of the peer-reviewed research to the design and implementation of their children's IEPs? Well, first, I needed to be clear as to what I mean by applying the peer-reviewed research, hence everything I just got through explaining.

Parents first need to understand what they are asking for and how it impacts the design and implementation of their child's IEP. Further, any professionals reading this for the purpose of further developing their skill set may not have all the background information necessary to make sense of all of this, either.

A foundation first had to be laid. Having now done that, parents need to keep the information I've just shared in mind when participating in IEP meetings and reviewing IEP documents for appropriateness.

If you live in a consent state like California, I usually suggest signing only for attendance at the meeting and taking the document home for review before signing agreement to any of it. In California and other states, you can give partial consent to an IEP and the education agency has to implement the consented-to portions without delay while the non-consented-to portions remain subject to IEP team discussion and negotiation.

Anything that can't be resolved via the IEP process must go to due process for resolution, whether you are in a consent state or not. Just because you are not in a consent state doesn't mean that an education agency won't change the language of an IEP at your request. An IEP meeting would likely be called to discuss your concerns and, if you back them up with facts and logic, the education agency isn't going to have a good reason to say, "No." Not everyone is outlandishly unreasonable in special education; there are some definite bad apples, but they don't account for the entire barrel. Due process is your only resort if your efforts to resolve things at the IEP level are not met with success and your child is increasingly compromised because of the unresolved matters.

If you are unfortunate enough to have to rely on due process to see things resolved, the fact that your denied requests were supported by facts and logic will only help your case once you get in front of a hearing officer. Understanding the underlying arguments of what makes something legitimately measurable and the federal requirement that special education be delivered according to what science has already proven works makes you a far more informed IEP participant than at least some of the other people at the table.

As a parent, the more you can support your requests and arguments with peer-reviewed research, the better. Once you frame your requests according to the proven science and make it as black-and-white as possible, you eliminate all kinds of silly arguments. This means not only asking for goals that are truly measurable, though that goes a long way towards solving and preventing a lot of problems, but also understanding the nature of your child's disability(ies) and what the research says can be done to teach to learners with such needs.

Gathering the necessary research data to inform a request for a particular assessment, service, curriculum, methodology, technology, or placement requires accessing the peer-reviewed literature and understanding what it means. A lot of it is really dry and technical, as well as expensive. This isn't a burden parents should have to take on, but if it's one that they can take on, it will only help them become better advocates for their children. Google Scholar can be a good place to start.

In truth, it should be education agency personnel doing this research, but if parents want to see the science applied, they may have to push for it, themselves. Parents can also submit published research articles to their local education agencies that appear to apply to their children's educational needs and request that the approaches used on those articles be used as part of their children's special education programs, including being written into their children's IEPs. If the local education agency declines to honor any request, 34 CFR Sec. 300.503 obligates it to provide Prior Written Notice (PWN) explaining why to the parents.

Conversely, if the education agency proposes a particular approach and the parents are unsure about it, the parents can request an explanation of the peer-reviewed research that underpins the education agency's offer. Either it honors the request or it provides PWN explaining why it won't. If it's the latter, it better be one heck of a good explanation or it will only reveal that the education agency has no research-based explanation for its recommended course of action, giving the parents a good reason to dispute it.

If what you are asking for as the parent is backed up by facts, logic, legitimate measurement, and credible research that all directly apply to your child, and the education agency still says, "No," then you will either end up with no PWN because the agency doesn't want to put the denial in writing, which violates the law and only makes your case stronger in hearing, or you will end up with a PWN full of malarkey that won't stand up in due process. If what you are asking for makes total sense and the education agency won't do it or something else equally or more appropriate, the education agency will have some explaining to do in hearing.

So long as what you are asking for is necessary for your child to receive an appropriately ambitious amount of educational benefits (meaning as close to grade level or developmental norms as possible), there's not a lot of good reasons for a public education agency to turn down your request. It's illegal for the public education system to use fiscal considerations to determine what should be in a special education student's IEP.

Just be sure to submit all of your requests for changes to your child's IEP in writing. It is the education agency's receipt of your written request for changes that triggers the PWN requirement. In the instance of requesting assessments, many states allow for a public education agency to decline to conduct assessments for special education purposes upon parent request, but the agency must provide PWN when doing so. For more information on special education assessments, see our previous post, "The Basics of Special Education Assessments."

If it doesn't decline a parent's written request for assessment, the education agency must provide the parent with an assessment plan to sign that authorizes the agency to conduct the requested assessments. State law regulates the provision of assessment plans; in California, local education agencies have 15 calendar days to get an assessment plan to the parent, regardless of who made the referral for assessment. Submitting the request for assessment in writing is not only important for triggering the PWN requirement if the request is declined, it's also important in establishing when a state-mandated timeline starts counting down.

You as a parent can encourage the application of science in special education by insisting upon it. If you live in California or another consent state, you can use your authority to withhold your consent to anything that looks sketchy in an IEP being given to you for your signature. You can consent to instruction in the areas targeted by IEP goals but not to using the language of the goals for the purpose of measuring progress if they aren't actually written in a measurable way. You can consent to everything in an IEP except a change in placement. If you can't resolve all of the issues you have with an IEP this way, those left unresolved become due process issues.

Even if you are not in a consent state, you can still make the record in writing that you disagree with the sketchy portions of your child's IEP, explain why using math and science, and request appropriate changes. The local education agency will likely call an IEP meeting and change those things it's willing to change and give you PWN on those things it is not willing to change. The things left unresolved at that point are due process issues.

Understanding how to use math and science to solve everyday problems is a solid skill to have, but not everybody has it. It's a skill necessary to developing a sound IEP for any special education student. Parent education can be provided as a related service under a student's IEP if the purpose of the parent education is to help the parents understand their child's disability and/or to help them be equal participants of the IEP team. There is absolutely nothing wrong with parents asking to be trained on how to write measurable annual goals and the IEP process in general as part of parent training as a related service under their child's IEP. Parent training is specifically named as one of many possible related services that can be provided to a student with an IEP by 34 CFR Secs. 300.34(a) and 300.34(c)(8)(i)).

If you're distrustful of the quality of instruction you might get from parent training through your child's IEP, you may have to result to self-education by reading everything you can find about your child's disability, as much of the peer-reviewed research about instructing learners with the types of needs your child has as you can digest, and simplified reports of the research findings in trusted publications from credible sources. You may need to periodically consult with experts for hire, but what you invest in informing yourself you may save many times over by preventing yourself from getting duped.

The bottom line is that parents can protect their children's right to evidence-based special education planning and implementation the more they understand how to use measurement and evidence in the planning and implementation processes. By knowing what to look for, they know what request when they don't see it. Informed parents can monitor the situation for education agency compliance.

In those areas where parents have not yet mastered the knowledge necessary to know whether an approach is appropriate for their child or not, they are encouraged to ask questions like, "Can you explain to me how this fits my child?" and "How can we measure whether this works in a meaningful way?" By shifting the burden back onto the education agency to explain how and why its recommendations are supported by the peer-reviewed research and written in an appropriately measurable manner, parents rightly shift the burden of applying the science to the appropriate party.

Parents are not, and should not, be required to become experts in order to participate in the IEP process. But, for the sake of protecting their children's educational and civil rights, and their own rights to meaningful parent participation in the IEP process, it behooves parents to become as knowledgeable as possible. It's more difficult to get tricked or misled the more you know, and the more dry and technical you can keep things, the less hysterical drama you're likely to experience in dealing with your local education agency.

References:

- Drasgow, E., Yell, M.L., & Robinson, T.R. (2001). Developing legally correct and educationally appropriate IEPs. Remedial and Special Education 22(6), 359-373. doi: 10.1177/074193250102200606

- Kimball, J. (2002). Behavior-analytic instruction for children with autism: Philosophy matters. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(2), 66-75. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F10883576020170020101

- Yell, M. & Drasgow, E. (2000). Litigating a free appropriate public education: The Lovaas hearings and cases. The Journal of Special Education, 33(4), 205-214. doi: 10.1177/002246690003300403

Thursday Nov 07, 2019

The Fundamental Flow of IEP Creation

Thursday Nov 07, 2019

Thursday Nov 07, 2019

Image credit: Justin Lincoln

Trying to piece together the actual special education process from the implementing federal regulations of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a lot like trying to create origami from paper shredder cuttings. However, it's been done and, when laid out in proper order, the special education process totally makes sense.

When followed as intended, the special education regulations are a marriage of law and science. It is further assumed that procedural compliance with the regulations is likely to result in the provision of the Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) promised to each special education student by the IDEA. The specific language comes from what is known in special education circles as "The Rowley Decision," which specifically states, "the Act's emphasis on procedural safeguards demonstrates the legislative conviction that adequate compliance with prescribed procedures will in most cases assure much, if not all, of what Congress wished in the way of substantive content in an IEP. "

In order to understand why the regulations require the things in special education they do, it helps to first understand the history of the language in the regulations. Prior to Congress enacting the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) in 1975, which ultimately became the IDEA during a later reauthorization, there were no laws that specifically promised any kind of education to children with special needs.

Prior to the EAHCA, children with disabilities were routinely denied enrollment into the public schools. In the beginning, it was an accomplishment just to get a public school to open its doors to a child with special needs, and there was nothing that made it mandatory to educate the child according to any particular standards once the doors had been opened.

Then, in 1971, disability advocates took the matter of the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Citizens (PARC) vs. the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to the U.S. District Court. The settlement and resulting consent decree produced much of the language that is now found in the implementing regulations of the IDEA, particularly with respect to FAPE and individualized educational program development.